From Three Mile Island to Fukushima Daiichi

Editor’s note: In this 50th anniversary year of IEEE Spectrum, we are using each month’s Spectral Lines column to describe some pivotal moments of the magazine’s history. Here we consider Spectrum’s coverage of nuclear disasters in two different eras.

Three years ago, a tsunami came crashing down on the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan, leading to the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl. As Associate Editor Eliza Strickland explains in this issue in “Dismantling Fukushima: The World’s Toughest Demolition Project,” that accident stillreverberates strongly in Japan, where all of the country’s nuclear plants are currently off line.

Strickland’s report continues a decades-long history at Spectrum of rigorous coverage of nuclear technology. A milestone was our November 1979 issue on the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in the United States. Though Fukushima and Three Mile Island were very different technically, the parallels between them are enlightening.

We started covering nuclear power back in July 1964, in our seventh issue, with an encyclopedic 11-page feature titled “Nuclear Power Today and Tomorrow.” It predicted that in the United States, “by year 2000, 45 percent of electric power will be nuclear” (the actual percentage turned out to bearound 20 percent). The article concluded that “experience to date, and a series of specific tests have shown that nuclear power is inherently safe. That the public be convinced of this is most important because the growth of metropolitan areas will result in a growing need for reactor plants in or near population centers.”

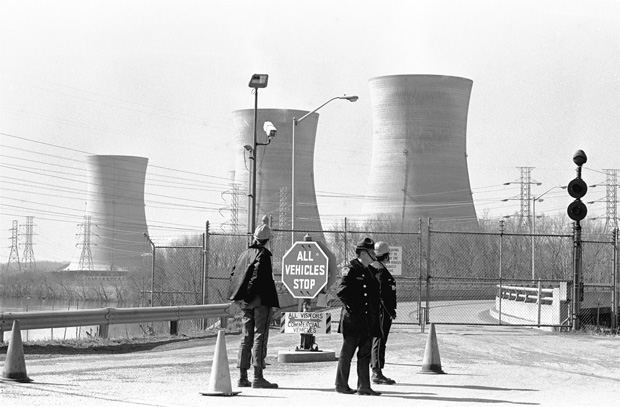

Ouch. It turned out that U.S. nuclear power would face considerably greater public-relations challenges. During the early morning hours of 28 March 1979, a cascade of improbable mishaps led to a partial core meltdown in a reactor at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, in Pennsylvania.

Some of the initial news accounts of the incident were atrocious: hysterical, wildly speculative, and wrong. There were suggestions that the plant was in imminent danger of blowing up like a bomb, prompting tens of thousands of people to panic and flee the area. Part of the problem was that, in the critical first hours, even the operators of the plant didn’t have a good grasp of what was happening inside the reactor.

Amid the chaos, Donald Christiansen, then IEEE Spectrum’s editor in chief, saw an opportunity. “He immediately felt we had a special obligation to try to determine what had gone wrong,” says Ellis Rubinstein, then a 34-year-old staff editor at Spectrum.

Christiansen directed Rubinstein to get to the bottom of the mishap, and gave him an unexpected suggestion. “Every journalist is going to go to Three Mile Island,” Rubinstein remembers Christiansen telling him. “They’ll all be competing with each other, and there will be a lot of noise and confusion.”

Christiansen’s advice was to skip that media circus and go instead to Babcock & Wilcox, the company that had manufactured the stricken reactor. “Get them to describe, step-by-step, what happened,” Christiansen told Rubinstein. “Draw a diagram of what went wrong,” he added. “When you can draw that diagram, you’ll be able to write the article.”

What happened next bespeaks a bygone era in journalism. Babcock & Wilcox not only agreed to cooperate, it gave Rubinstein an office to use at the headquarters of its nuclear division, in Lynchburg, Va. Staff members tutored him on nuclear power technology and gave him regular updates on what they were discovering, through data collection and simulations, about exactly how the mishap unfolded.

It is inconceivable that a company would offer a journalist such access in today’s world of litigation and mistrust. For example, shortly after the 2011 accident, Strickland requested interviews with officials at Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO), the utility that operates Fukushima Daiichi, but she was rebuffed for months. Ultimately, during her first reporting trip, she was granted only a single and largely uninformative one-hour interview.

Rubinstein made the most of his time in Lynchburg. Staying in a nearby motel and speaking daily with experts at Babcock & Wilcox, he pieced together an exhaustive account of exactly what went wrong. He checked everything he learned with nuclear experts in government regulatory agencies, other nuclear companies, and academia. “You can’t always trust your sources. Even if they mean well,” says Rubinstein, who is now president and CEO of the New York Academy of Sciences.

With Rubinstein’s own article as its core and with a dozen other articles edited by him, Spectrum’s 1979 report was the first journalistic account to give a minute-by-minute description of the accident. It was so thorough that the first official U.S. government report, which was released within a day or two of Spectrum’s issue, had no substantial facts or details that were not inSpectrum’s coverage.

The Three Mile Island accident was rated a 5 on the seven-level International Nuclear and Radiological Event scale; both Fukushima and Chernobyl were rated 7. Subsequent analysis indicated that the Three Mile Island accident released fewer than 13 million curies, most of it in the form of relatively harmless radioactive noble gases, as well as 13 to 17 curies of radioactive iodine. This paltry amount of released radioactivity could have no measurable impact on the health of the local population, experts said. Not bad, overall, considering that roughly half of a reactor’s core had melted down.

Although there were no apparent health effects, there were certainly financial ones. The cleanup at Three Mile Island cost about US $1 billion and took 14 years. The much more complicated Fukushima cleanup will result in costs, including lost economic assets and opportunities, of up to $250 billion, according to a Japanese survey. For comparison, the country of Belarus has estimated that the damages associated with Chernobyl will total $235 billion.

The Three Mile Island accident also plunged the U.S. nuclear industry into a dormancy from which it began stirring only recently and rather sluggishly. In 2012, for the first time in 35 years, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved a nuclear construction project, at the Southern Company’s Vogtle plant in Georgia. The Vogtle project, which is installing two new reactors, is one of three such construction projects in the United States. Still, don’t count on a U.S. renaissance in nuclear power, at least not anytime soon. Thanks to the boom in shale gas, natural-gas-fired electricity is a bargain. And in 2010, the Obama administration abandoned long-stalled efforts to build apermanent nuclear waste repository in the state of Nevada. Thus nearly 60 years after the start of commercial nuclear power, the United States has no clear plan for the long-term disposal of its 65 000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel, which will continue to be radioactive for thousands of years to come.

But Japan faces even greater challenges, as Strickland reports in this issue. The decommissioning of Fukushima Daiichi’s six reactors, including the three that melted down, will take 40 years and cost untold billions of dollars. “TEPCO freely admits that they don’t know how to do this,” Strickland says. “They have yet to invent the robots and remote systems that will let them take apart these highly radioactive reactors.” And then there’s the matter of whether Japan’s 48 remaining operational reactors are safe enough to reopen.

Spectrum’s rigorous coverage of nuclear issues has not gone unnoticed. That 1979 Three Mile Island issue, proposed by Christiansen, with articles by Rubinstein and Christiansen and editing mostly by Rubinstein, wonSpectrum’s first National Magazine Award, the highest honor in U.S. magazine publishing. And a 2011 article by Strickland about Fukushima—a blow-by-blow account very similar in its wealth of detail to Rubinstein’s Three Mile Island story—was a pillar of our fifth such award, in the category of “General Excellence.”

More important, these stories give engineers and other tech-savvy people the kind of information they want on events of enormous import. Speaking of Christiansen, who was an engineer before becoming a publisher, Rubinstein says: “He realized that a lot of journalism in the technology and science world was about what goes right. He knew that you can often learn a lot more by studying what went wrong.”